More than ten years ago I published an article on Alexander the Great in the political discourse of the 19th century Levantine national movements when he struck a chord with the masses and was the perfect historical poster child for all manner of independence efforts from the Ottoman Empire.

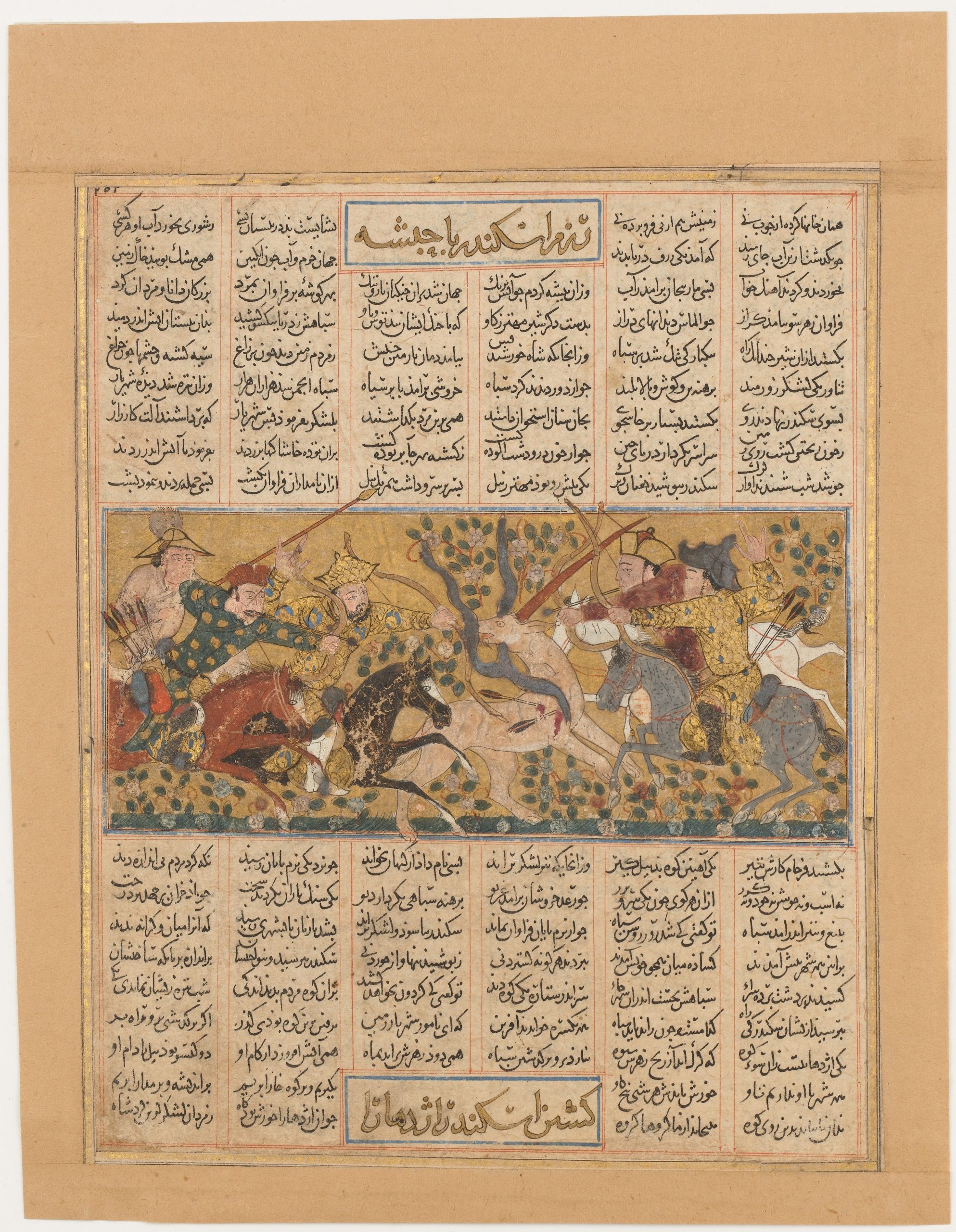

The article (in German, open access) examines Alexander’s popularity in a specific context, harkening back to centuries of literary engagement in Europe and the Middle East. In Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, his popularity was immense and inspired generations. Shrouded in mystery, Alexander became the hero of numerous adventurous stories.

Alexander is even mentioned in the Qur’an, albeit not explicitly. However, Islamic tradition leaves no doubt that ḏū l-qarnayn, the two-horned, is about Alexander, who is said to have seen himself as the incarnation of Dionysus, the Greek deity whose roots lie in India and whose attribute, among others, is the horn.

While for centuries Alexander was hailed for being a leader who connected East and West, modern nationalist movements invoked his name for their own ends and against territorial claims by competing national movements. Either way, Alexander’s reverberations in literature are at least as marvelous as his real-life quest ever was.

In Persia, Alexander became a Persian prince while Arab historiographers identified his country of birth Macedonia as Egypt. Thankfully, the British Library has curated an exhibition called Alexander the Great: The Making of a Myth (Link) that sheds a light on all these aspects. It’s definitely worth a visit given that it’s available online and without a paywall. Some of its topics are:

☞ The Alexander romance (link)

☞ A Russian manuscript of the Alexander Romance (link)

☞ Turkish manuscripts on Alexander the Great (link)

☞ Alexander the Great in Firdawsi’s Book of Kings (link)

☞ The emperor and the Sun King (link)

☞ Iskandar’s encounters with women (link)

Alexander’s reported demise is no less spectacular: After crossing India and Persia, he moved to Iraq where he died as young as 32 years of age (for reasons that are disputed to this day). His body was carried in a golden shrine to Alexandria, the city he founded. After subjugating the ancient world, he has been traveling through the darkness ever since.

Literature:

Kreutz, Michael, 2013. Das Ende des levantinischen Zeitalters: Europa und die östliche Mittelmeerwelt. Hamburg: Kovac.

Lewis, Bernard, 1975. History: Remembered, Recovered, Invented. Princeton: P. University Press.

Radtke, Bernd, 1992. Weltgeschichte und Weltgeschichtsschreibung im mittelalterlichen Islam. Beirut: Ergon.